The origin of the village of Winlaton Mill is open to conjecture but before the arrival of Ambrose Crowley the hamlet was called Huntley’s Haugh. The Winlaton Manor was in the ownership of the Neville family but parts of it were leased out. It had a mill that was both a corn and a fulling mil, there was also a corn mill on the south side of the river owned by the Hardings of Hollinside. The miller in 1700 was George Evans and the area became known as Evans Banks and later Eels Haugh. Until the time of Crowley’s there were only about half a dozen houses occupied by families named; Hunter, Atkinson and Smythe..Ambrose Crowley having set up his iron works at Winlaton after a few years, as the nail business grew, found that it wasn’t economical to be dependent upon slitters in the Midlands for supplies of rod iron. He wrote ‘ A mill of my owne I will have’. The factory at Winlaton was unsuitable and he found the ideal place a mile east of Winlaton alongside the swift flowing River Derwent, the exact date of development is not known but in surviving records Crowley refers to it as ‘The Mill’ or ‘Mill No 1’ and we know some building was finished by the winter of 1697/8 because he was trying to sell some surplus 3” planks which he had bought to shore up the river bank. In 1700 there are more references in Crowley’s administrative letters about the cost of the buildings. By 1701 there were a plating forge, several smiths’ shops, a steel furnace and offices and by 1703 a slitting mill had been added. The original factory at Winlaton continued to be the headquarters.

He employed locals and advertised around England for skilled smiths.The two factories were each formed around a square with living quarters and workshops.There was a large wooden gate at the entrance for works traffic and a little wicket gate for pedestrians.Each craftsman worked independently, drawing bar iron from a common stock and delivering his finished product to the Crowley wharehouses..then goods shipped in Crowley vessels to London.Crowleys warehouse was at Blaydon Burn, built 1701 , and Crowleys became notorious for dodging the tariffs imposed by Newcastle for shipping goods down the Tyne. The workers’ lives were governed in every detail by the Law book which had some 117 laws ( of which 94 survive ) – the laws designed by Ambrose to control large scale industrial production from a considerable distance. Each square was in the charge of a timekeeper known as the warden of the mill – he had to see that all carriages were out of the square before candle light and that the great gate was shut and locked after dark – so the people who lived in the squares were locked in at night. The warden had to ring the bell for the start of work at 5am and 3 hours later ring the second bell for breakfast – ½ hour allowed. Dinner was from 12 till 1 then work carried on till 8pm – except Saturday when they were allowed to finish at 7pm – an 80 hour week, each window had to be high enough so that the workers could not look out, no daydreaming for Crowley’s crew.

In 1842 a bridge on three pillars was built to cross the river, one of the masons being Jack English, ‘Lang Jack’ as he was commonly known. This bridge was renewed in 1950 at a cost of £1600.00. A Wesleyan chapel was built in 1870 although since the beginning a room at the works had been reserved for daily prayer with services performed by the firm’s chaplain.

The site worked until the mid-late nineteenth century and was later overlaid by coal waste from the nearby Clockburn Drift which had re-opened in 1850 and by the Derwenthaugh Cokeworks built in 1928. Excavation in 1992 showed some survival beneath the coal waste and has exposed a considerable element of an eighteenth century dam, with associated spillway and race. The Winlaton Mill Works stood deserted for many years until it was finally demolished in 1936.

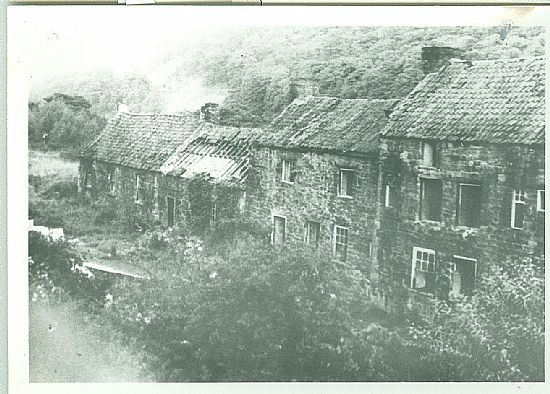

The old houses of Winlaton Mill, although picturesque in appearance, were over 200 years old and declared unfit for human habitation and a new village was built across the road. Building began in 1933 and was complete by 1937 while the old village was demolished.