The Martin’s Memories series has been reproduced with the very kind permission of Tony Martin from his posts on the Old Blaydon and Old Winlaton Facebook group.

OLD Blaydon and OLD Winlaton | MARTIN’S MEMORIES 7 | Facebook

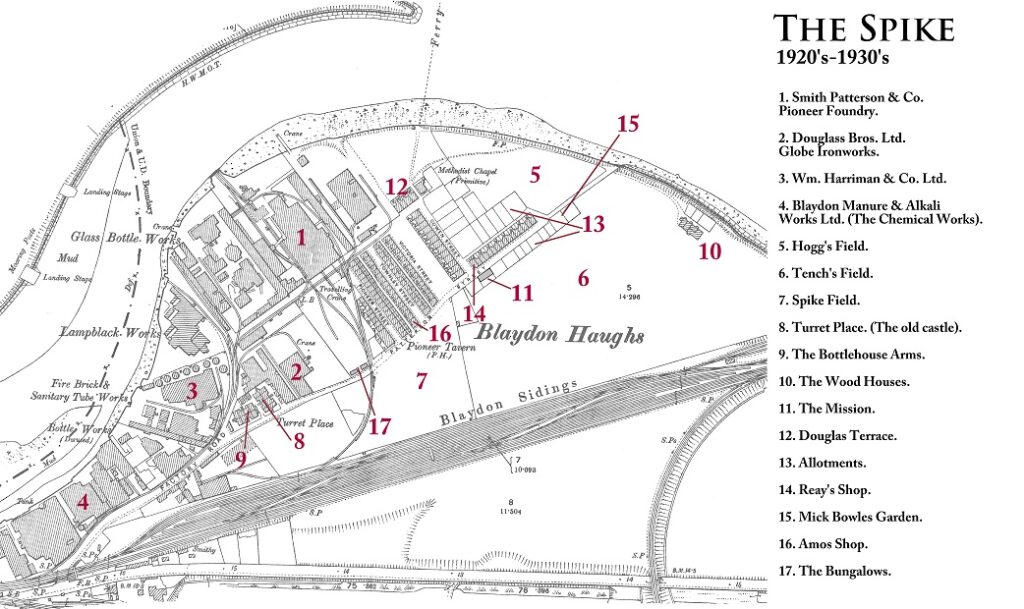

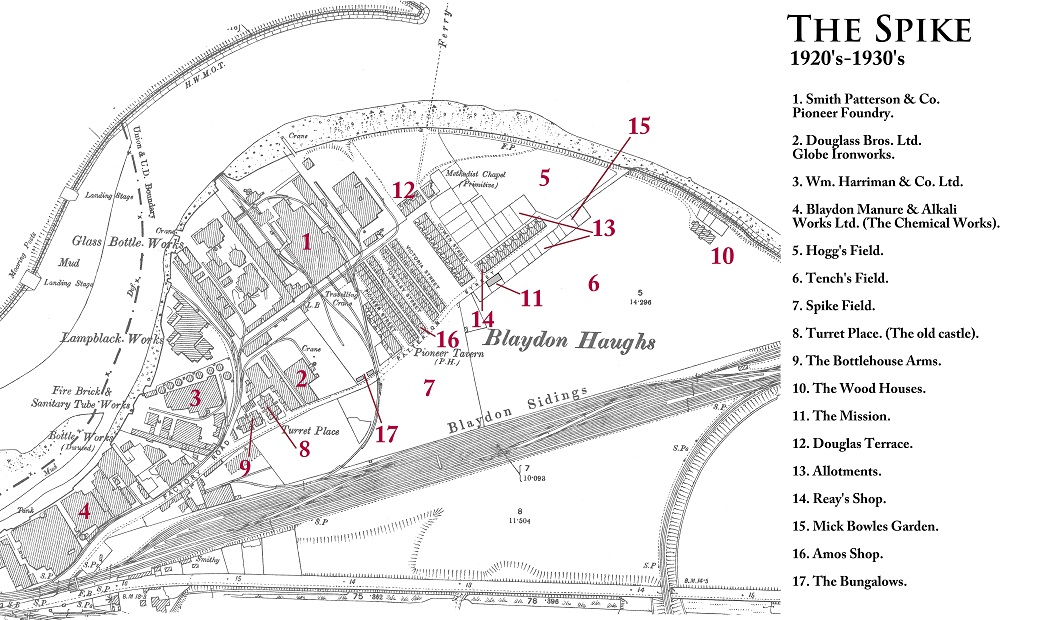

The Spike or Blaydon Haughs to give it its real name, was an area with a strong sense of community, situated in what was once the industrial heart of Blaydon along the river bank and separated from the rest of Blaydon by the railway. My first experience of this area, so different from what I had been used to, was when I was taken by Uncle Stephen, who had been born on Pioneer Street as the seventh of eight children of John Hands and his wife, Hannah Henderson. His mother died when he was just five and the family, now living at 9, Patterson Street, were cared for by Mary, the second eldest child. Mary later married Thomas Nevens and they had a son Tom and a daughter, Hannah, married Haddon. They used to visit my uncle and aunt in Park Avenue quite often and I also remember visiting them in Linwood Avenue in my childhood.

My uncle was educated at the school in St Cuthbert’s Place before moving to the Board School (later known as Blaydon East). He left school at 14, but could not begin an apprenticeship until he had reached 15. His father, who had been born at Pathhead and had served his time as a moulder, moving with Smith Patterson from Blaydon Burn to the Spike and so he got a job for him on a friend’s farm there. This entailed walking to and from Pioneer Street to Pathhead each day. On 10 January 1894, he commenced his apprenticeship at Smith Patterson. I still have the apprenticeship agreement which includes a special birth certificate issued under the Factory and Workshop Act 1891.

When I was young he used to tell stories of life on the Spike and the factories that had been located there. Stories of him being sent to various parts of the North East on jobs for the factory and later how he was often sent further afield to attend to the engines of the company’s ship. Evidently it did not have a resident engineer on board and he used to show me the postcards, he had sent my aunt, from his travels. Some of them intrigued me very much, including a story about the ship breaking down in Loch Long and he had taken the train to Whistlefield and the ship’s boat had picked him on the shore and taken him aboard to undertake a repair. He would also tell how the factory made railway chairs (the fittings that hold railway lines onto the sleepers) and we would also hunt for signs of Smith Patterson products whenever we were visiting other places. Unfortunately, he had passed away before I discovered perhaps the most remote location for a SP product….a sign post on a single track road near Strontian in Sunart…..something I did not discover until my daughter started courting the son of a forrester there.

Trips to the Spike made a lasting impression on me. We would always have to cross the footbridge at the foot of Thomas Terrace and then that over the main line to get the first of the factories, Fison’s Fertilisers which seemed always to emit a ginger brown, vile smelling smoke. Next came Harrimans, the firebrick and sanitary pipe manufacturer. When we got to the first of the pubs, the Bottle House Arms, he would tell stories of Turret Place, which the pub had replaced, and the people he had known there. Past Douglas Brothers and the Pioneer Tavern, we came to the terraced houses and I was shown the houses that he and various members of the family had lived in the 1880s and then to Patterson Street where he had lived until he was married in 1902. He told stories about the Blacking Factory (the Lampblack Works) and the Bottle Works and how, as a lad, he had scavenged among the scrap glass and managed to extract glass balls from bottle tops which he used as marbles. Opposite Patterson Street was the Plastic Factory, where I was to return in my Blaydon West days because the football pitch used by the school, was behind it and at one end of the pitch lay part of the engine sheds, which were also a train spotter’s haven in the 1940s and 1950s.