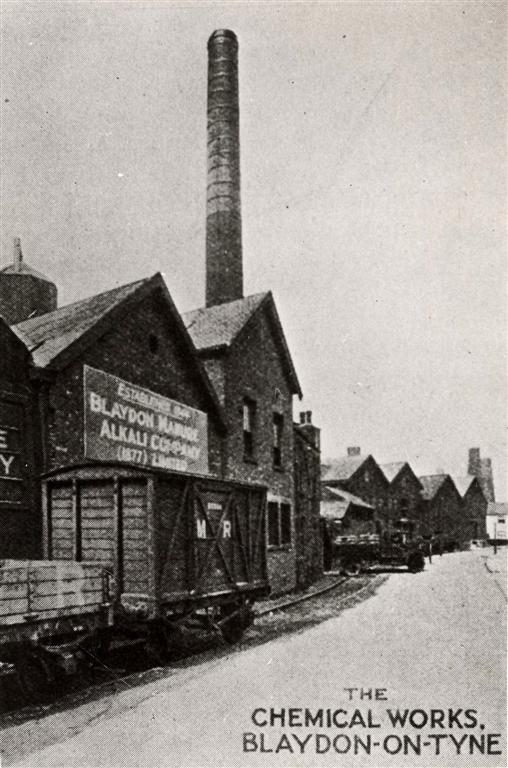

The Blaydon Manure & Alkali Company’s chimney, known locally as ‘The Chemical’, loomed over Blaydon town centre in my childhood, until its closure in the early 1960’s, emitting malodourous fumes and a display of multicoloured flames that easily rivalled the lightshows of psychedelia a decade later. As a child the place terrified me.

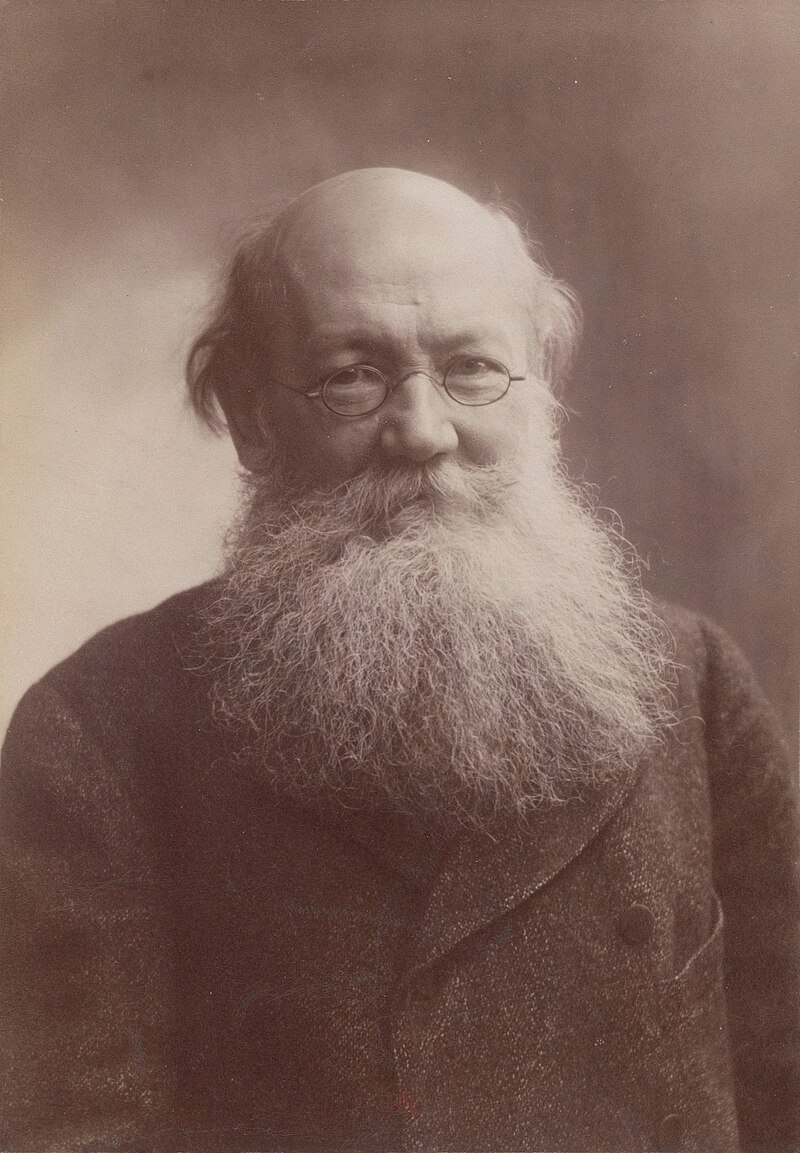

Years later I discovered that ‘The Chemical’ had more significance than just another source of local pollution, particularly to Peter Kropotkin, the famous Russian anarchist and advocate of autarchy, who discussed the plant in his Fields, Factories and Workshops, 1898. This international bestseller had numerous reprints and served as a manual for anarchist and other radicals who advocated communal self-sufficiency. The book was in many ways a precursor of the Whole Earth Catalog of 1968 with an emphasis upon utilising traditional skills along with anything that may be of use from modern industry and science.

‘Waste not Want not’ and recycling was a guiding principle in Kropotkin’s utopian masterplan and he was continually drawn to examples of small producers combining traditional methods with modern innovations. Jersey potato growers were singled out as exemplars of this principle by fertilising their fields with free seaweed gathered from local beaches and artificial manure shipped in from Blaydon upon Tyne, this formula producing a crop famous for its unique flavour and texture, grown on relatively poor-quality soil.

Kropotkin was a frequent visitor and had longstanding Tyneside connections with northern radicals such as Joseph Cowen, the Newcastle MP, industrialist and former Chartist supporter and would have known that the Blaydon factory belonged to the Priestman family, Cowen’s close neighbours.

The Priestmans were a dynasty of mining engineers, colliery and industrial owners with a penchant for discovering new products. ‘Blaydon Benzol’ produced at their plant close to Cowen’s brickyards was the world’s first petroleum spirit produced from coal; and their tar works had a valuable sideline in manufacturing ammonia powder, a vital element in their fertiliser. Kropotkin enthused at such integration and listed the other ingredients, including large amounts of dung and bones from a variety of sources, especially mummified cats from Egypt, another vital source of the white stuff, offloaded at their factory wharf, which also served to ship their product to Jersey potato growers, their largest market. This mixture was blended, then fired by small, low value coal from their nearby mines, creating a distinctive odour to our town centre air.

One evening I stood watching green flames dancing at least twenty feet above the chimney. I later learnt that they also used locally mined barium for a new product developed in wartime at government prompting for use in photography, the Ilford company remained a customer when hostilities ended. My mother obviously knew something I didn’t, and as I watched green, blue, yellow and orange flames pirouetting in the early evening sky from the pavement outside Joe Sapperetti’s café, she became alarmed and shooed me quickly up Church Street to catch the bus to the higher ground of Winlaton and safety.

In recent years I’ve noticed, although it may be my age, that ‘Jersey Royals’ have little flavour and their texture has lost some of its waxiness, and similar to strawberries their season now lasts for many months. No doubt the Channel Island producers, much admired by Kropotkin, now utilise a different fertiliser.

Bill Lancaster, 2025

From an article submitted to the London Review of Books in response to James Vincent’s review of White Light: The Elemental Role of Phosphorous, by Jack Lohman.